Panic, Revisited (Part 2)

Editor's note: This is part 2 of a two-part series. Part 1 is titled 'Panic, Revisited (Part 1)'.

About a week after I first visited Sutter Sacramento hospital in mid-2016, my electro-cardiologist Dr. Krishnan Subramaniam, who fitted the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) into my chest, interrogated my ICD. He observed that a few days earlier (Sunday) the ICD had successfully treated a few irregular heartbeat events, at least one of which would have been fatal to me, were it not for the ICD’s intervention.

Risk of sudden cardiac arrest

Also, it was at that moment that we discovered that I had long been at risk of sudden cardiac arrest due to irregular heartbeats known ventricular tachycardia or “v-tach”. What happened is that I showed the doctor a copy of an EKG print I had kept with me from my first stay at the hospital.

While under continuous heart monitoring, my heart started to misfire dangerously, but only for a short period. The nurse on call ran into my room and asked if I had felt anything peculiar in my chest - I had not. Then, on instinct, I asked him to give me a printout of the event. That is the EKG print I had kept in a file and showed to the doctor.

After consulting with my cardiologist Dr. Xu Zi Jian, Dr. Krishan adjusted my medication to help the electric signals of my heart to fire at a normal rhythm.

Regrettably, I had already reached advanced heart failure. I didn't get better with the therapies I left the hospital with. The incapacitating effect of my condition was increasingly beginning to show. My heart’s ability to function had changed drastically in a short time—my heart muscle had severely deteriorated, which explained why I was now easily becoming winded and would need to stop to catch my breath after going up just two flights of stairs or for a short run.

Acute decompensated heart failure

As an athletic and active person since childhood and someone who continued to practice many sports, I was demoralized to find myself increasingly confined to bed. Over the next two weeks, I went to the ER at Sutter Sacramento two other times, but the urgent care specialists dismissed me thinking I only had some gastrointestinal (GI) issues. So, the following time I felt my symptoms worsening, I called the Advanced Cardiology team and talked to the nurse-on call while on my way to the ER to make sure on this fourth visit to the ER, I was seen by the right team.

Ultimately, I was diagnosed with “acute decompensated heart failure,” which meant I had already reached the end-stage or advanced heart failure. My ejection fraction (EF) was now around 11% and my ProBNP above 9000. My liver and kidneys were starting to get affected. There were other issues as well. After undergoing an additional test, they found severe pressure in my heart and lungs and determined that I had a “reduced cardiac index (CI)”. Cardiac output (CO) is the volume of blood the heart pumps per minute and CI is a function of CO value based on the patient’s size. The normal range for CI is 2.5 to 4 L/min/m2 but mine was 1.1. This meant that my heart was performing at less than half of normal capacity.

Miracle juice

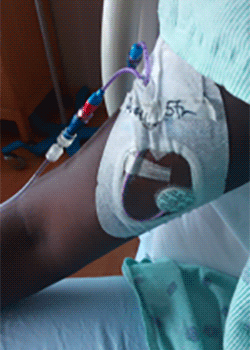

I was put on more furosemide diuretics drips and another intravenous (IV) medicine—Milrinone Lactate—which turned out to be a true “miracle juice.” My symptoms largely resolved within a day and I started feeling better. I remained asymptomatic for the remainder of the hospitalization. Little did I realize that I would soon need to adjust to another significant lifestyle change. Because of my low cardiac index, the care team determined that I needed to keep taking Milrinone. Three weeks later, I was discharged with a 24-hour Milrinone mobile infusion—a unit that allowed me to continuously take the medicine via infusion—as a transition to further care.

Join the conversation